In recent years, the Savilian professorships at New College have continued to grow in prominence, reflecting a wider trend throughout the university.

Today, the Department of Astrophysics at the University of Oxford is one of the largest in the country, internationally recognised for its work on cosmology, galaxy evolution, and the study of exoplanets. Geometry, too, is a key department within the Mathematical Institute—again one of the largest mathematical departments in the United Kingdom with cutting-edge research conducted in the areas of algebraic geometry, Riemannian geometry, and symplectic geometry. In this final section of our exhibition, we celebrate the most recent history of the Savilian Professorships, explore the work of the most recent incumbents in the two posts, before finishing with a look at the latest research in both areas of study and how both subjects could affect our day to day lives in future decades.

In 2019, New College celebrated the 400th anniversary of the Savilian Chairs—an occasion to celebrate the past as well as to look forward to the future. In part to facilitate future research, the New College SCR decided to purchase an operational, modern telescope to commemorate this anniversary. Pictured on the right, it is a Celestron Advanced VX-25 Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope, combining the benefits of a reflecting mirror with the compactness, portability, and low-maintenance of a refracting lens. The diameter of the aperture is 9.25"; being the widest aperture compatible with the portability requirements—this allows the maximum possible collection of light. The telescope also has an advanced VX ‘goto’ mount, allowing it to locate and track stars automatically across the sky. The SCR was advised on various aspects of the purchase by Katherine Blundell OBE, Professor of Astrophysics at Oxford and Professor of Astronomy at Gresham College. The telescope was purchased from Harrison Telescopes with funds provided by the Emmerson bequest. An aspiration of the purchase is that a ‘Star Clerk’ be appointed from amongst the fellowship, to be responsible for the upkeep and operation of the telescope.

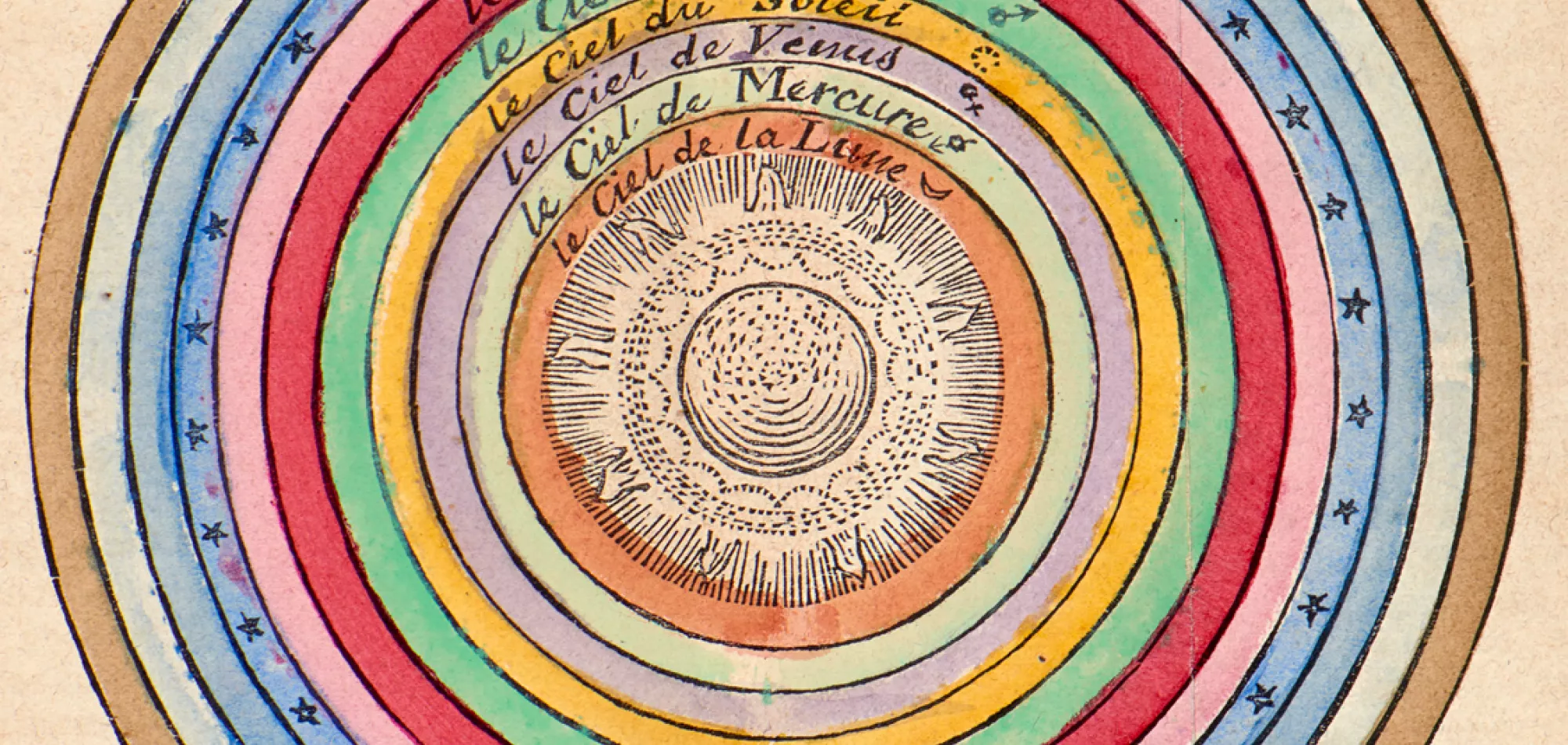

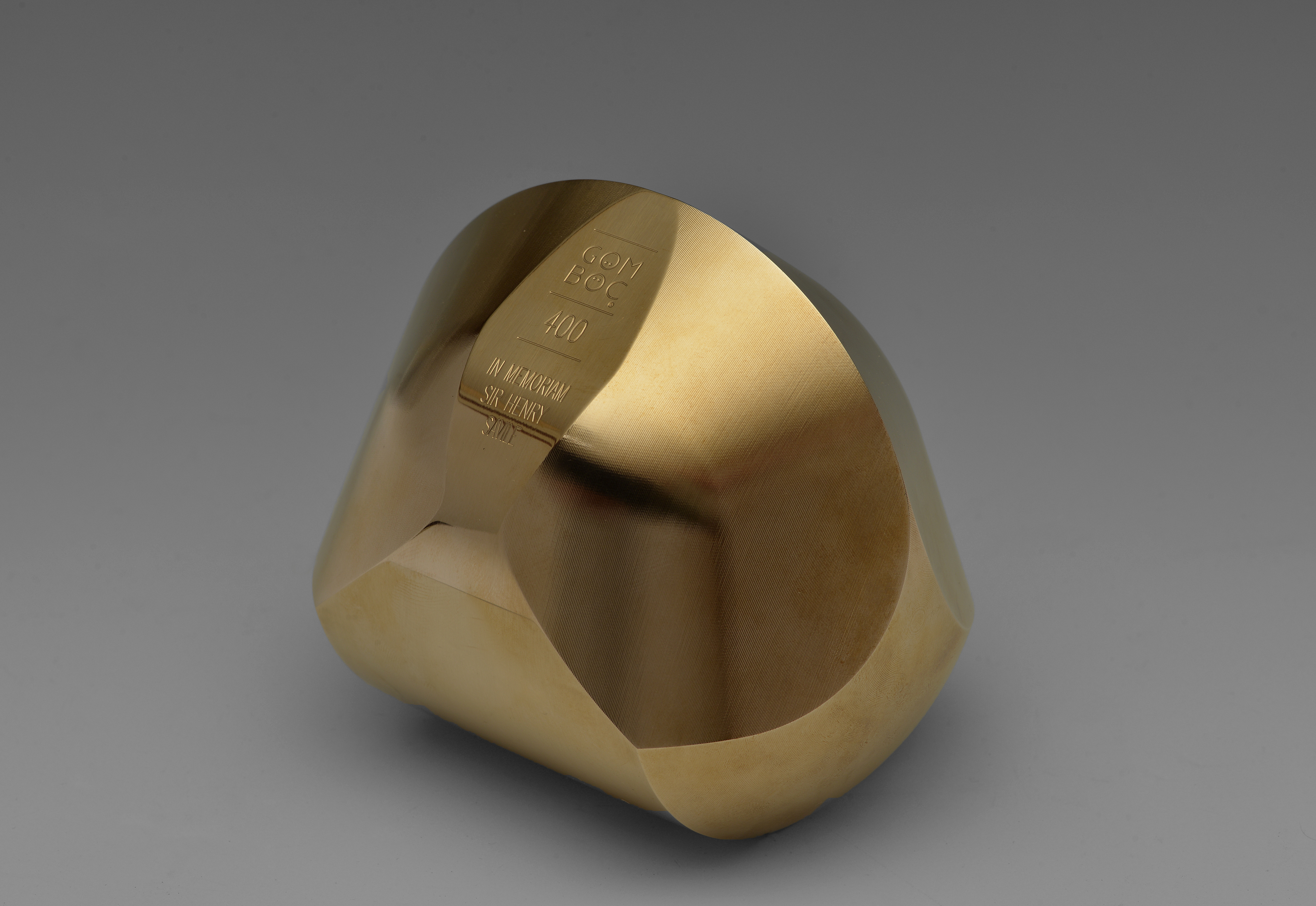

To accompany the telescope, the SCR also commissioned a ‘Gömböc’ for geometry, pictured on the left. The Gömböc is a paradox, a work of art, and the answer to a deep mathematical question. Imagine a pebble living in a two-dimensional world, such as a profile drawn on paper. The pebble can be of arbitrary shape provided no point on the surface dents inward. It is easy to convince yourself, and straightforward to prove, that if the pebble is homogenous it must have at least two stable, and two unstable, points of balance. It cannot have one. In 1995, it was conjectured that there may exist a three-dimensional shape which does balance on precisely one point. After a decade of work, two Hungarian mathematicians, Professors Gábor Domokos and Péter Váronyi, found the shape. They named it a Gömböc (pronounced roughly gumbuts), a diminutive of gömb, sphere.

To accompany the telescope, the SCR also commissioned a ‘Gömböc’ for geometry, pictured on the left. The Gömböc is a paradox, a work of art, and the answer to a deep mathematical question. Imagine a pebble living in a two-dimensional world, such as a profile drawn on paper. The pebble can be of arbitrary shape provided no point on the surface dents inward. It is easy to convince yourself, and straightforward to prove, that if the pebble is homogenous it must have at least two stable, and two unstable, points of balance. It cannot have one. In 1995, it was conjectured that there may exist a three-dimensional shape which does balance on precisely one point. After a decade of work, two Hungarian mathematicians, Professors Gábor Domokos and Péter Váronyi, found the shape. They named it a Gömböc (pronounced roughly gumbuts), a diminutive of gömb, sphere.

Numbered individual Gömböcs may be commissioned as one-off works of art. Consisting of 99.99% pure silver, G1619 was commissioned by New College SCR to mark the 400th anniversary of the founding of the Savilian Chair of Geometry. The commission, overseen by Professor Domokos himself, was made possible by a number of generous donors: Mr Ottó Albrecht of Hungary, and funds once again from the Emerson bequest. The creation of a silver Gömböc presents a significant challenge, and will take years to complete. To coincide with the quarter-centenary itself, Mr Albrecht commissioned G400 in bronze, engraved with the inscription ‘IN MEMORIAM HENRY SAVILE’.

In recent years, the Geometry Chair has been occupied by two exceptional Professors. The first, serving as Savilian Professor of Geometry between 2017 and 2024, is Dame Frances Kirwan, whose main fields of study are algebraic and symplectic geometry. Before coming to New College, Kirwan held a junior fellowship at Harvard, a Fellowship at Magdalen College, Oxford and a Fellowship at Balliol College, Oxford. A Fellow of the Royal Society, Kirwan has won several prizes throughout her career, including the London Mathematical Society Whitehead Prize in 1989, the Maths and Computing Suffrage Science award in 2016, and the Sylvester Medal of The Royal Society in 2021.

In November 2024, the Oxford Mathematical Institute announced that Professor Dominic Joyce has been appointed as the New Savilian Professor of Geometry—he will be the 21st holder of the position. Also a Fellow of the Royal Society, Joyce has been working at Oxford for many years, completing a BA and DPhil at Merton College, followed by a Junior Research Fellowship at Christ Church, a University Lectureship at Lincoln College, and—most recently—a professorial post in the Mathematical Institute from 2006. Like Kirwan, he researches algebraic and symplectic geometry, but is also interested in differential geometry.

Since 2012, Professor Steven Balbus has served as the Savilian Professor of Astronomy. A noted astrophysicist who studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of California, Berkeley, Balbus's research is in the area of theoretical astrophysics. In the Geometry and Astronomy publication from 2019, he described his research as broad:

His research into MRI (magnetorotational instability) has been particularly lauded. In 2013, he won the distinguished Shaw Prize for his work in this area with Professor John F. Hawley. More recently, Balbus has been the recipient of the Eddington Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society and the Dirace Medal and Prize of the Institute of Physics.

All of this new research, combined with ever more powerful technological advancements, has the potential to transform many aspects of our day to day lives. The most cutting edge research in the area of geometry today, for example, focuses on atomic-scale geometry—investigating the properties of geometry at a truly microscopic scale. This area has the potential to revolutionise the future of electronics, creating a path to superconductivity and, in turn, hastening the arrival of quantum computing. Unlike classic computers, quantum computers can run on quantum bits, or qubits, which have the potential to make them much more powerful than regular computers.

Likewise, the development of artificial intelligence has the potential to revolutionise geometry. Compared with text-based AI models, geometry has been difficult for AI to understand, as there is significantly less training data available. Google DeepMind, though, has now worked to solve this issue, creating an AI system that can solve complex geometry problems. This new system is a significant step not just for geometry, but for wider artificial intelligence, as it helps in the development towards machines with human-like reasoning skills.

Likewise, the development of artificial intelligence has the potential to revolutionise geometry. Compared with text-based AI models, geometry has been difficult for AI to understand, as there is significantly less training data available. Google DeepMind, though, has now worked to solve this issue, creating an AI system that can solve complex geometry problems. This new system is a significant step not just for geometry, but for wider artificial intelligence, as it helps in the development towards machines with human-like reasoning skills.

The future of the field of astronomy is no less exciting. As the technology behind telescope design becomes ever more advanced, increasing amounts of raw, complicated data will be gathered both from telescopes on the Earth's surface as well as from telescopes in orbit. Combined with new computing tools and artificial intelligence, the techniques to analyse this quantity of data will improve massively—techniques which can be equally applied to complex data sets in other fields.

These ever more accurate telescopes also have the potential to alter our understanding of the universe and to promote the development of human space flight programmes. NASA’s planned Habitable Worlds Observatory, for example, is a space telescope designed to search for exoplanets—planets that have the potential to be the home of extra-terrestrial life or as destinations for future interplanetary travel. A visualisation of an exoplanet can be seen above. As the Apollo space programme helped to improve technology across multiple areas, it is hoped that new advancements in astronomy will also have a similar effect, creating technology with potential applications across a whole range of sectors on Earth.

Henry Savile would be astonished by recent progress in his two favoured fields of geometry and astronomy. With the establishment of his two professorships over four hundred years ago, he definitely looked towards the future. It is likely, therefore, that he would be equally excited for the developments to come in both these fields, especially with the onset of artificial intelligence. As this exhibition has shown, Savilian professors have always made a lasting contribution to science. As the twenty first century progresses, future Savilian chairs will no doubt continue to do so.