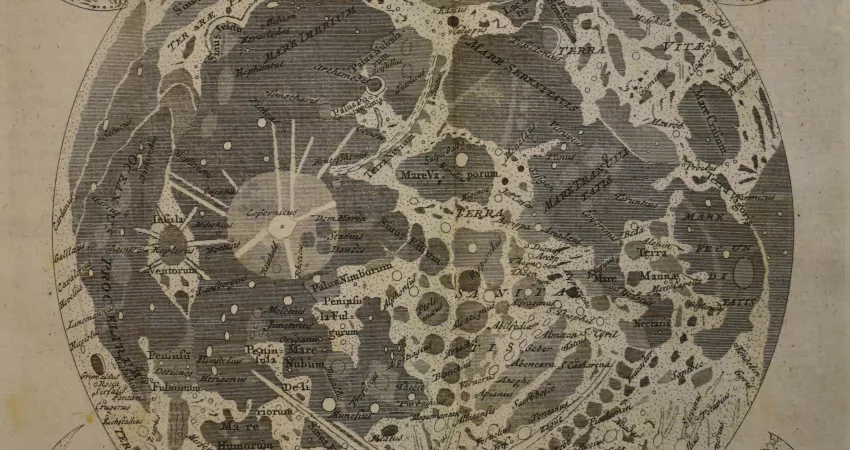

Today, the collections cover the development of the discipline from its Ancient Greek origins right up to the research published by the Savilian professors themselves.

Deriving from the ancient Greek geo, meaning earth, and metron, meaning measurement, this branch of mathematics is one of the most influential in the history of humanity. First developed in Mesopotamia and Egypt to tackle practical problems resulting from the development of agriculture and trade, it was the Ancient Greeks that revolutionised geometry, not only coining the word itself, but more importantly putting it into a logical framework for the first time.

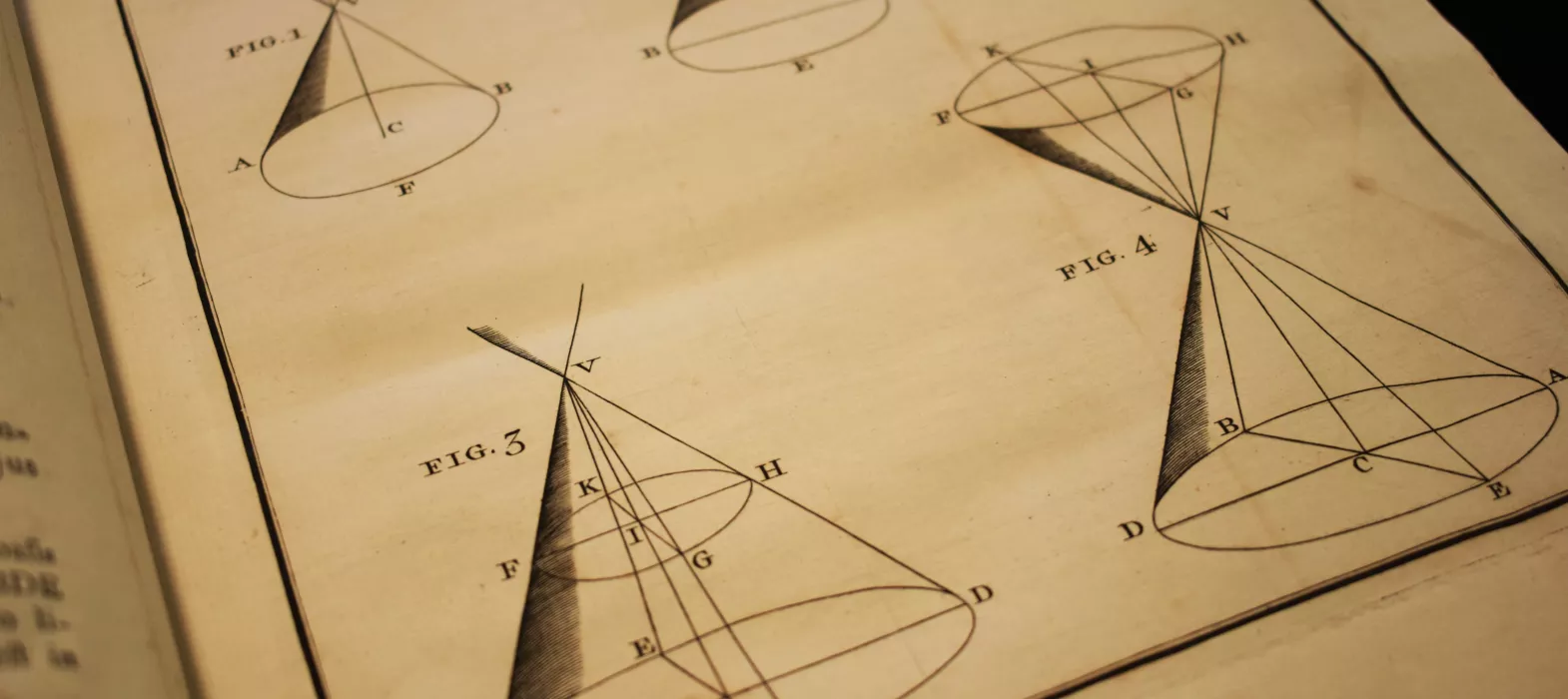

The most important Greek geometer has to be Euclid—his statue in the Natural History Museum in Oxford is depicted to the right. Building upon earlier geometric knowledge, Euclid revolutionised the subject with the publication of his Elements, which effectively put geometry into a logical framework. Starting from clear building blocks like points and lines, he made a series of assumptions, now called axioms or postulates, which could be proved with examples. Considered to be one of the greatest works compiled by man, Euclidean geometry was extremely influential. The Euclidean tradition is still visible in Newton's Principia Mathematica and Einstein even praised Euclid over two thousand years later, writing that his assertions 'could be proved with such certainty that any doubt appeared to be out of the question. The lucidity and certainty made an indescribable impression on me.’

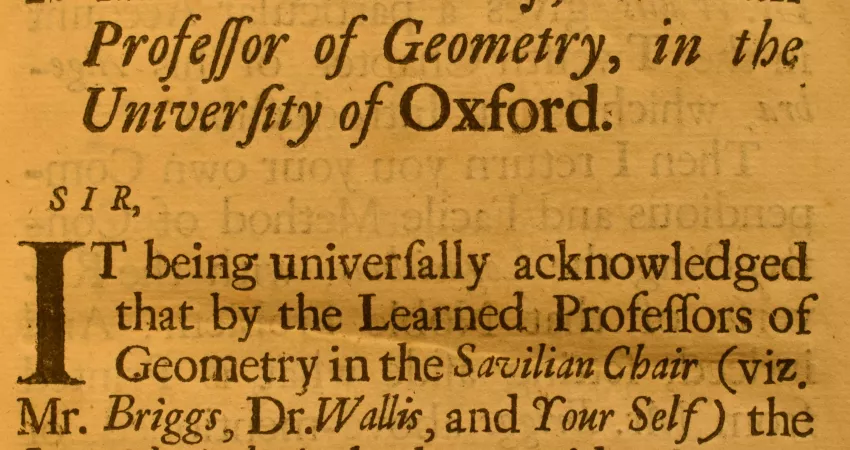

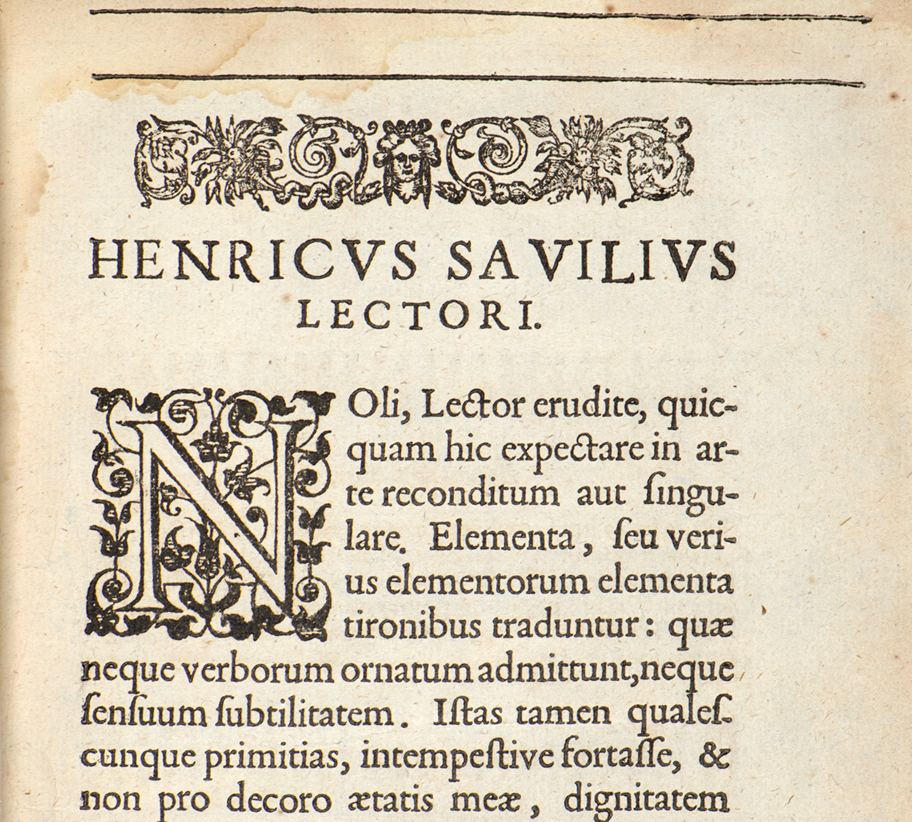

As Euclid is such an important figure in the history of geometry, it is not surprising that he is well represented in New College Library's collections. Indeed, even Henry Savile himself lectured on Euclid, as you can see pictured on the left here. The book preserves Henry Savile’s lecture series on Euclid in

As Euclid is such an important figure in the history of geometry, it is not surprising that he is well represented in New College Library's collections. Indeed, even Henry Savile himself lectured on Euclid, as you can see pictured on the left here. The book preserves Henry Savile’s lecture series on Euclid in  As Euclid was so influential, all undergraduates studying for the BA in the medieval and early modern periods were supposed to master at least the first six books of Euclid. Not much, though, is known about how geometry was actually taught in the university. The two books pictured here provide us with a glimpse into this teaching. Both were owned by the same man, Daniel Appleford, who studied in the college in 1645.

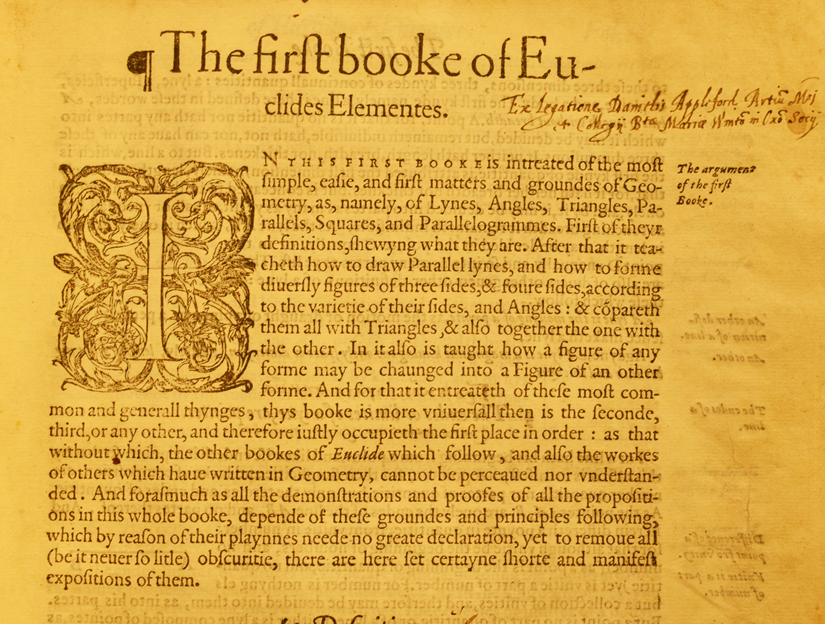

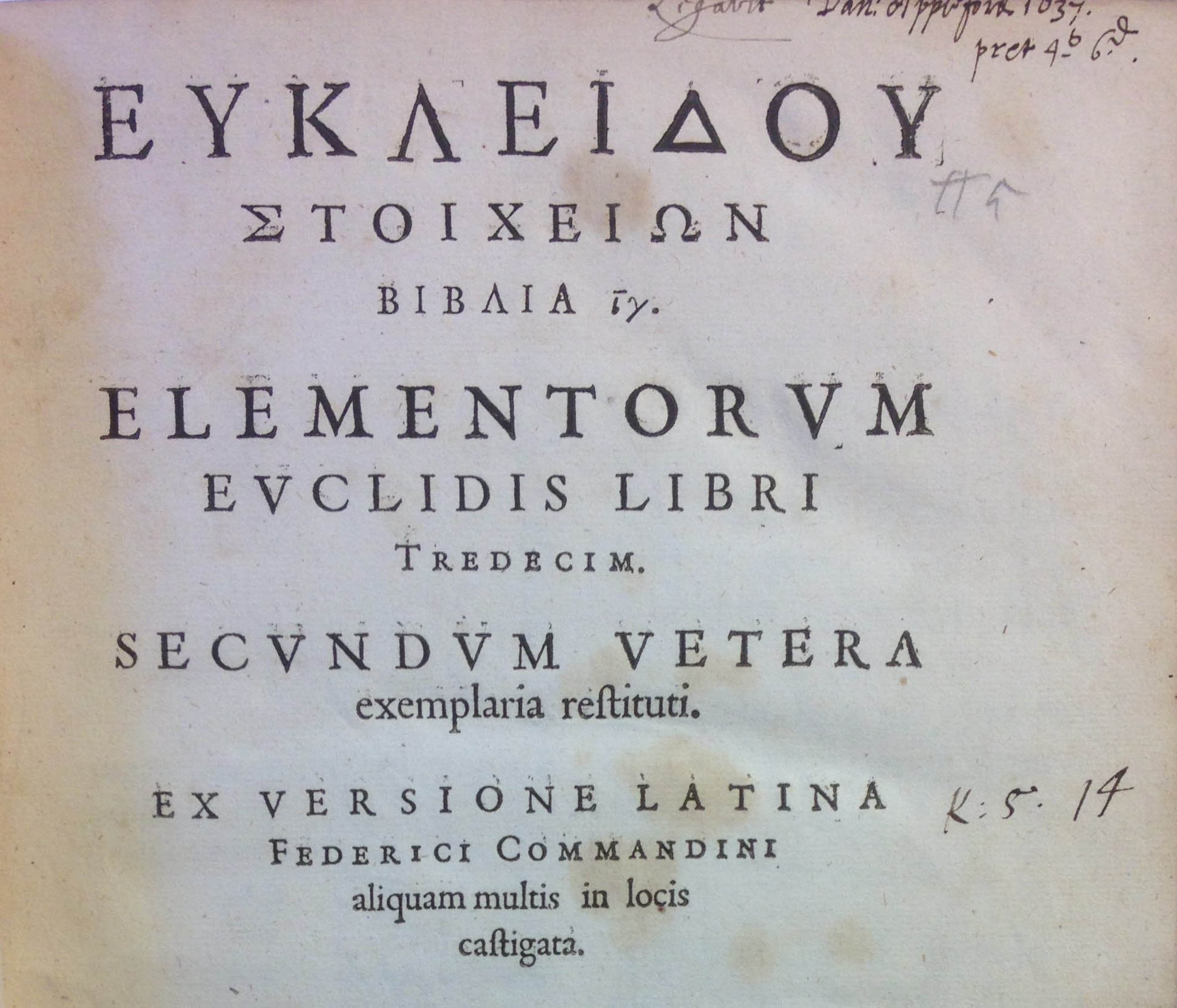

As Euclid was so influential, all undergraduates studying for the BA in the medieval and early modern periods were supposed to master at least the first six books of Euclid. Not much, though, is known about how geometry was actually taught in the university. The two books pictured here provide us with a glimpse into this teaching. Both were owned by the same man, Daniel Appleford, who studied in the college in 1645. The first, pictured on the right, is the London 1570 translation of Euclid into English,

The first, pictured on the right, is the London 1570 translation of Euclid into English,