Easily the most famous astronomical manuscript in New College Library’s collections is MS 281, a thirteenth-century manuscript copy of Ptolemy’s Almagest. This work, completed before 147 AD, soon became the authoritative textbook of theoretical astronomy. The thirteen books cover the full range of mathematical astronomy, from arguments on the Earth’s spherical shape to eclipse theory and calculations of the longitudes and latitudes of constellations. In it, Ptolemy also developed a planetary model, known as the Ptolemaic system. A geocentric model, it argued that the planetary bodies and the sun orbited around the Earth, the centre of the known universe.

Easily the most famous astronomical manuscript in New College Library’s collections is MS 281, a thirteenth-century manuscript copy of Ptolemy’s Almagest. This work, completed before 147 AD, soon became the authoritative textbook of theoretical astronomy. The thirteen books cover the full range of mathematical astronomy, from arguments on the Earth’s spherical shape to eclipse theory and calculations of the longitudes and latitudes of constellations. In it, Ptolemy also developed a planetary model, known as the Ptolemaic system. A geocentric model, it argued that the planetary bodies and the sun orbited around the Earth, the centre of the known universe.

Ptolemy’s work had an interesting route to the West. It was translated into Arabic around 800 AD, leading to parallel transmission in Arabic and the original Greek. Our fourteenth-century manuscript belongs to the former tradition, featuring Gerard of Cremona’s influential Latin translation from Arabic, completed c. 1175.

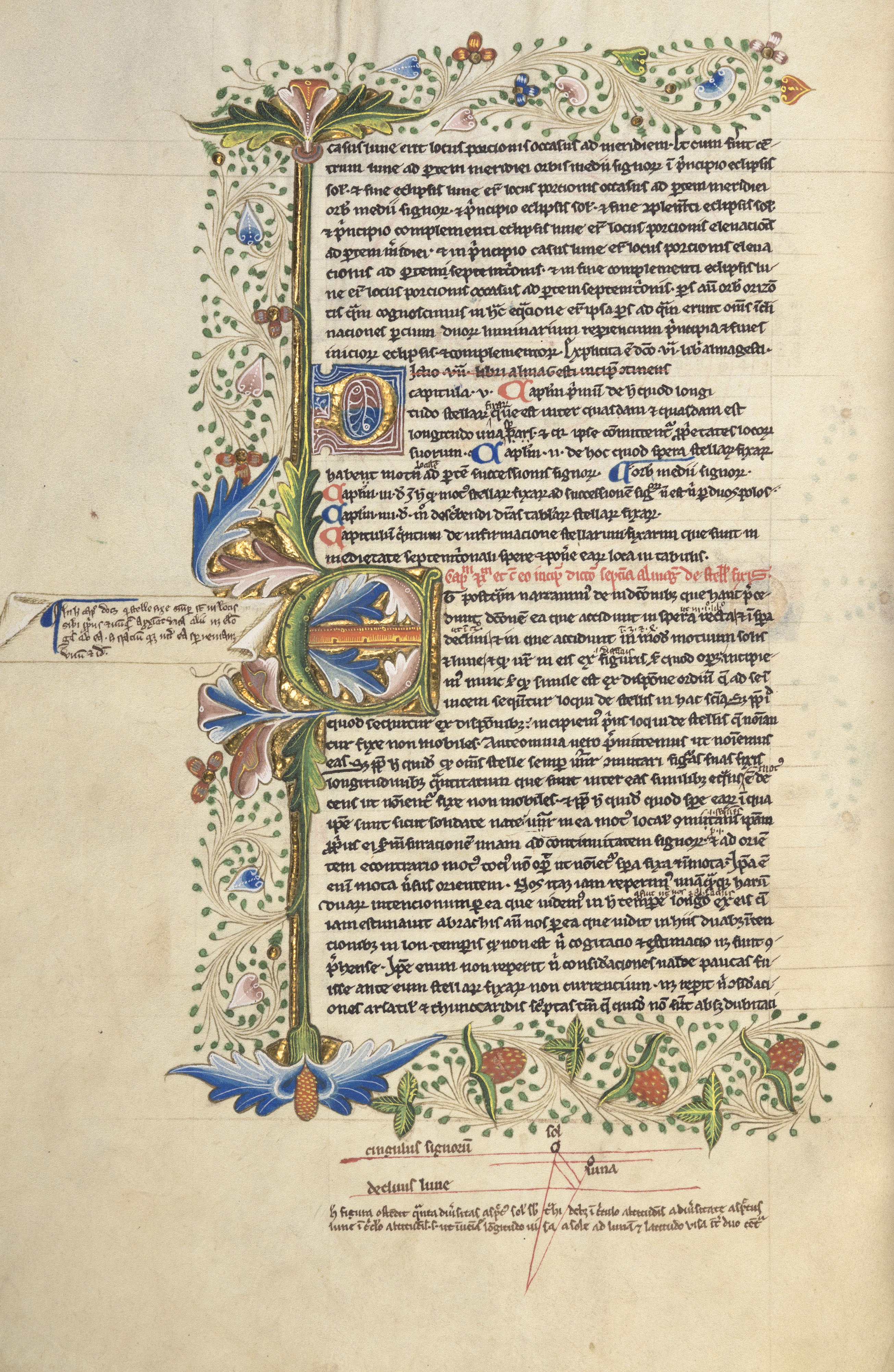

The manuscript, as you can see in the image of folio 122v to the right, is particularly beautiful, illuminated on several different pages, with copious use of gold. Note the intricately depicted strawberries in the border decoration, shown in enlarged form below.

Unusually, this lavish decoration is much later than the manuscript itself, added nearly two centuries after it was first made. The standard geometrical diagrams that accompany the text were the only illustrations included in the original, and this is perhaps explained by its provenance. We know that the manuscript was donated to the college by John Farley, a New College alumnus who was university registrar from 1458 until his death in 1464. It seems probable that Farley had this manuscript specially illuminated in preparation for giving it to New College.

Consequently, this very manuscript may have been used by Henry Savile as part of his early astronomical studies. Savile had first applied himself to Ptolemy after pausing his studies of Euclid, which he had found overly taxing. He began reading the Almagest in the original Greek, but the difficulty of the mathematics forced him to revisit Euclid. Bolstered by the geometrical understanding from this further study of Euclid, he returned to Ptolemy. This attempt was far more successful, so much so that he worked on a new translation of Ptolemy into Latin, perhaps referring in the process to this Latin manuscript copy in the Library at New College. His translation was never published, but does survive in manuscript form in the Bodleian (MSS Savile 26–28). Like for many astronomers, Savile’s study of Ptolemy was a foundational part of his education, making this manuscript copy in the Library a key piece of astronomical history.

Easily the most famous astronomical manuscript in New College Library’s collections is MS 281, a thirteenth-century manuscript copy of Ptolemy’s Almagest. This work, completed before 147 AD, soon became the authoritative textbook of theoretical astronomy. The thirteen books cover the full range of mathematical astronomy, from arguments on the Earth’s spherical shape to eclipse theory and calculations of the longitudes and latitudes of constellations. In it, Ptolemy also developed a planetary model, known as the Ptolemaic system. A geocentric model, it argued that the planetary bodies and the sun orbited around the Earth, the centre of the known universe.

Easily the most famous astronomical manuscript in New College Library’s collections is MS 281, a thirteenth-century manuscript copy of Ptolemy’s Almagest. This work, completed before 147 AD, soon became the authoritative textbook of theoretical astronomy. The thirteen books cover the full range of mathematical astronomy, from arguments on the Earth’s spherical shape to eclipse theory and calculations of the longitudes and latitudes of constellations. In it, Ptolemy also developed a planetary model, known as the Ptolemaic system. A geocentric model, it argued that the planetary bodies and the sun orbited around the Earth, the centre of the known universe.

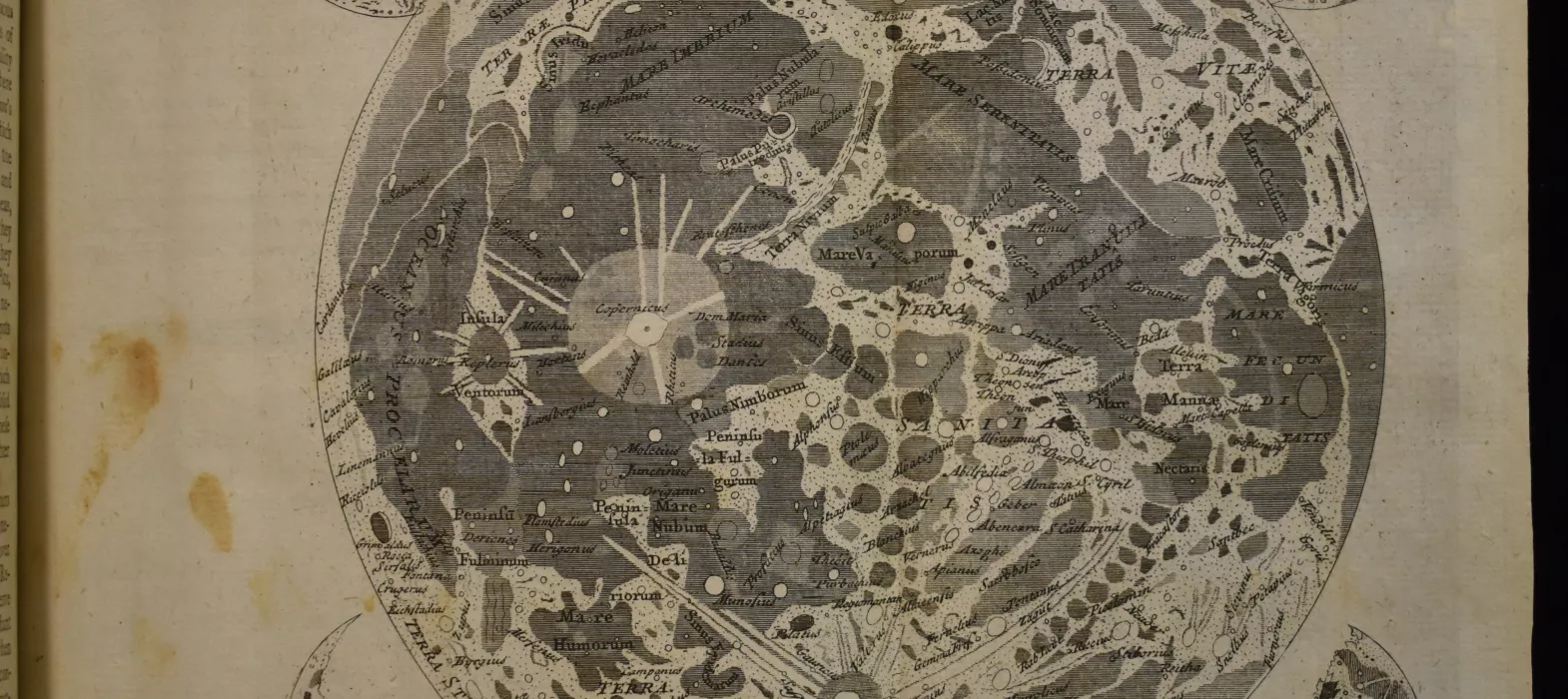

As technology developed following the Renaissance, classical astronomy started to be challenged by a new generation of astronomers. New scientific ideas around accurate and repeated observations, as can be seen in another page from the Astronomicum Caesareum on the right, led to a wealth of new data, which in turn led to the development of new ideas around the solar system, especially when this data was later combined with new technologies such as the telescope. A range of theories were proposed—some tried to use science to corroborate the classical and Christian approved geocentric model, whilst others started to challenge traditional viewpoints. This battle was, of course, played out in the written word—with New College Library today holding many of the works relevant to this debate.

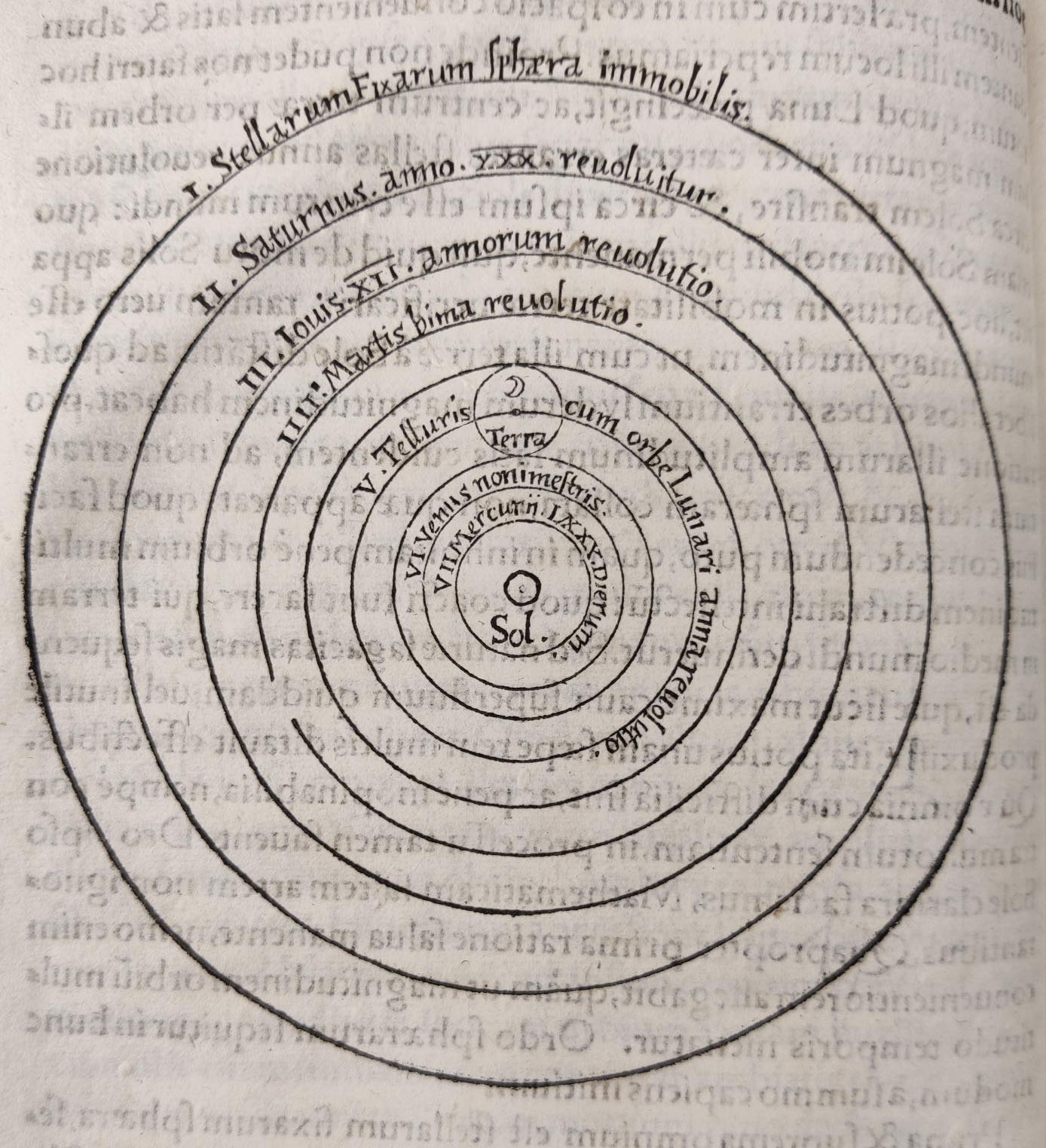

As technology developed following the Renaissance, classical astronomy started to be challenged by a new generation of astronomers. New scientific ideas around accurate and repeated observations, as can be seen in another page from the Astronomicum Caesareum on the right, led to a wealth of new data, which in turn led to the development of new ideas around the solar system, especially when this data was later combined with new technologies such as the telescope. A range of theories were proposed—some tried to use science to corroborate the classical and Christian approved geocentric model, whilst others started to challenge traditional viewpoints. This battle was, of course, played out in the written word—with New College Library today holding many of the works relevant to this debate. When first published in 1543, Nicholaus Copernicus’s De Revolutionibus changed astronomy forever. In it, he publicised his heliocentric model of the solar system to a wider audience for the first time. This model was in direct opposition to contemporary thought—and a direct challenge to the established geoecentric model developed by Ptolemy in antiquity, discussed above. Instead of the Earth being the centre of solar system, Copernicus correctly argued that the planets orbit around the Sun, and not the Earth, also proving that the moon revolves around the Earth. The famous diagram of his model within the text is pictured on the left. A widely read text, it was soon published in multiple editions, with the

When first published in 1543, Nicholaus Copernicus’s De Revolutionibus changed astronomy forever. In it, he publicised his heliocentric model of the solar system to a wider audience for the first time. This model was in direct opposition to contemporary thought—and a direct challenge to the established geoecentric model developed by Ptolemy in antiquity, discussed above. Instead of the Earth being the centre of solar system, Copernicus correctly argued that the planets orbit around the Sun, and not the Earth, also proving that the moon revolves around the Earth. The famous diagram of his model within the text is pictured on the left. A widely read text, it was soon published in multiple editions, with the