Victorian Britain was a time of profound change.

At the end of Victoria’s long reign, her kingdom would have been almost unrecognisable to those alive when she ascended to the throne. It was a time when the industrial revolution reached its climax, when the British Empire expanded greatly, and when new technologies such as the railways and industrial printing revolutionised travel and communication forever. Thanks in part to these societal changes, it was also a period of tension, with marginalised groups battling the dominance of the ruling classes—creating a gradual movement towards reform.

As we have seen in previous centuries, literature produced across the country reflected these changes throughout Victorian society. Thanks to the introduction of compulsory education, increased prosperity, and the embedding of a network of circulating libraries, printed material reached an increasing number of people, reflecting contemporary society—and its problems—to a much wider audience. Below, we take some examples from this period in New College’s collections to highlight some of these changes, both bibliographical and societal.

Probably the most famous author of the Victorian period was Charles Dickens (1812–1870), who needs almost no introduction.

The son of an assistant clerk in the navy pay office, Dickens’s writing catapulted him to global fame, with the author selling thousands of tickets for his public readings in the 1860s, both in the United Kingdom and the United States.

A prolific author, in total he wrote fifteen novels, five novellas, and hundreds of short stories. In part due to the financial difficulties his family faced in his early life, he is particularly remembered for his sympathetic depictions of the working poor in London. Some of his characters, such as Oliver Twist, Bob Cratchit, and Pip are household names today. There can be few other English writers, apart from Shakespeare, with such a widespread influence.

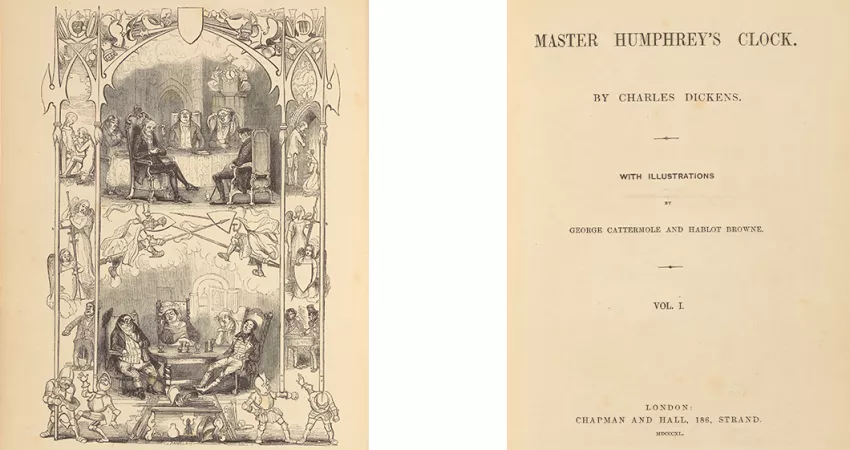

New College Library is fortunate to own some early works by Dickens. Below, you can see the title-page of the first published edition of Master Humphrey’s Clock. This title-page is taken from the first volume of a total of three (a so-called three-decker), all now held at New College Library. Dating from 1841, the volumes contain both short stories and two novels—The Old Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge. Both novels are emblematic of Dickens, as they explore themes present in much of his work: the impact of poverty, the importance of family, and the changing relationship between town and country in the face of rapid industrialisation. Click on the dots to discover more about this work:

The top of this frontispiece illustration presents an image of the late eighteenth-century as a Golden Age, with comfortable editors sitting around a table.

At the bottom, you can see that the editors have perhaps drunk too much, and are now asleep. The first volume illustrations are deliberately generic, with later illustrations more relevant to the text.

Chapman and Hall were the first publisher for Charles Dickens from 1840 until 1844 as well as his publisher from 1858 until 1870.

New College Library, Oxford, RS5268-RS5270

This work, like many of Dickens’s early works, was originally published as a weekly serial. A literary development that surged in popularity during the Victorian era, the serialized novel was published in a magazine in instalments, with a new part released every issue. Publishers often used serials to substantially lower the cost for each part and hence make the novel more accessible to those on a lower income. As each part had to keep the reader interested, this format even influenced the way that authors wrote, with each part often ending on an exciting cliffhanger.

The three volumes are bibliographically interesting because they retain the full and correct ordering of the texts as they originally appeared in the serial, with each of the larger novels interspersed with short stories. Dickens had originally wanted to keep this original order, but later anthologies mostly published the short stories and the novels separately.

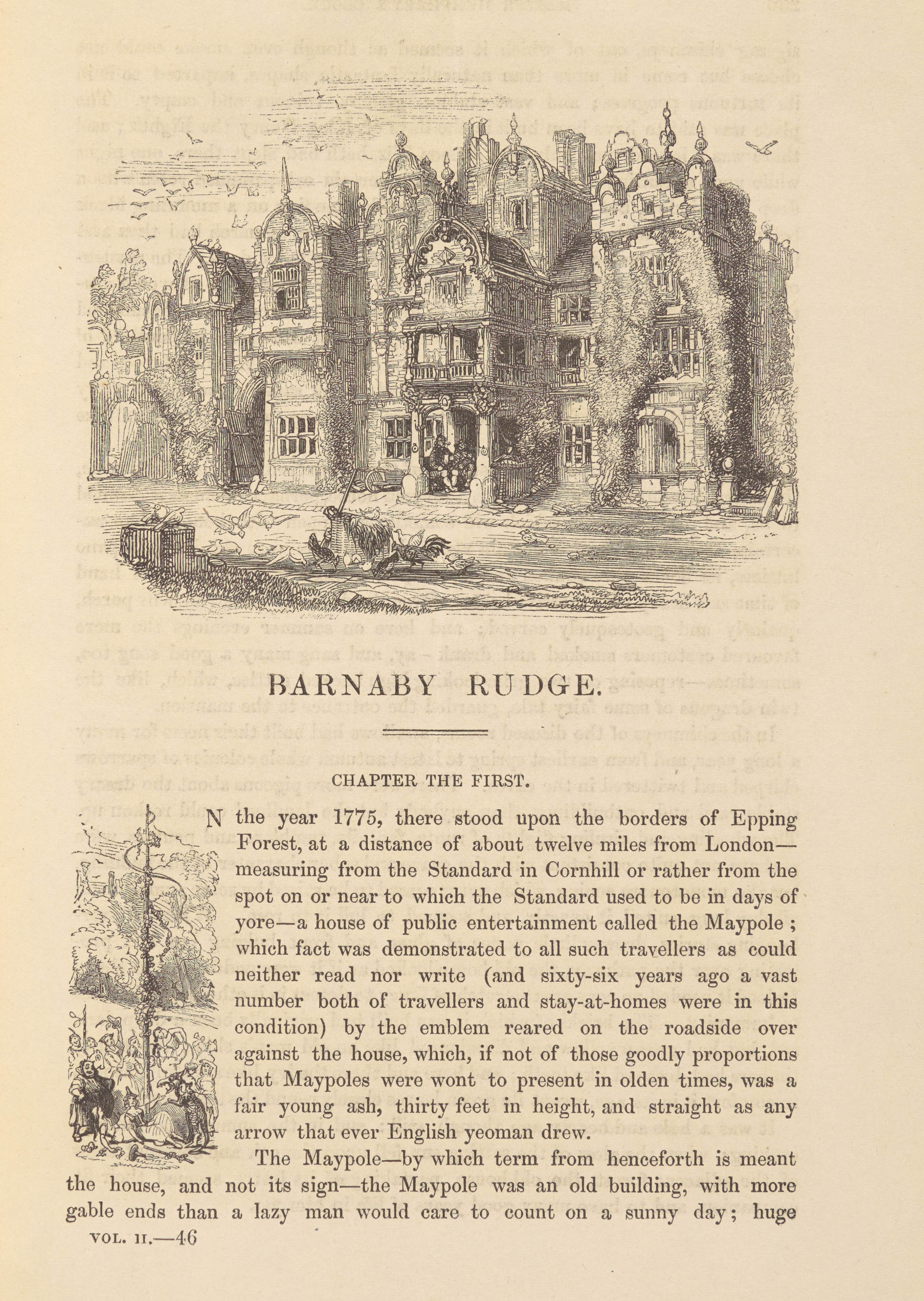

Above, you can see the first page of Barnaby Rudge. Dickens’s first historical novel, it is largely set during the Gordon Riots of 1780—a period of rioting in London motivated by anti-Catholic sentiment. It was the fifth of Dickens’s novels to be published, but initially it had been planned for it to be the first. Changes of publisher had led to many delays, leading to its later appearance in Master Humphrey’s Clock.

The text is greatly enhanced by its illustrations, such as the one shown here depicting the riots in great detail (p. 241). Dickens commissioned the illustrators George Cattermole (1800–1868) and Hablot ‘Phiz’ Browne (1815–1882) for Master Humphrey’s Clock, with both illustrators having very successful careers as a result of their association with Dickens’s work.

The serial novel pioneered by Dickens soon spread.

Indeed, many successful authors in the Victorian period used serials to release their work—which often affected their bibliographical history. Is the first edition of a book, for example, the first serial part or the first published edition of the entire novel? Likewise, as texts were often substantially edited prior to release in a book format, which text should be considered the original?

A perfect example of the importance of these distinctions can be seen in the works of Thomas Hardy (1840–1928) in New College’s collections—often considered to be the greatest English novelist of the nineteenth century. New College owns, for example, the first published complete edition of Hardy’s novel Jude the Obscure, which appeared as a book on 1 November 1895 (post-dated 1896). The simple yet elegant title-page can be seen below.

Jude is the tale of a working-class, self-educated man who fails to gain admission to Christminster University, a fictionalised version of Oxford. Interestingly, New College itself appears in the final chapter of the novel, pictured below. Here, New College is renamed as Oldgate College, under whose archway Jude’s ruthlessly hard-headed and sensual wife Arabella enters, to observe men ‘putting up awnings round the quadrangle for a ball in the hall that evening’. She finds the place ‘rather dull’ (clearly an assessment of Arabella herself, not the college), and quickly returns to the streets of Christminster.

Jude the Obscure perfectly shows the bibliographical complexity of serial publications from this era. The novel had originally been published serially in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine from December 1894 to November 1895 in a bowdlerized form (i.e. with offensive material removed), as Heart’s Insurgent. Jude itself first appeared in its full form in the New College copy above, published by Osgood, McIlvaine and Co. in their edition of Hardy’s Wessex novels. Which text, though, should be taken to be Hardy’s original?

Upon its publication, the novel scandalised Victorian critics, who derided it for its immoral treatment of religion, class, education, sex, and marriage. Due to this reaction, it is now proverbial that Hardy abandoned writing prose following the savage criticism of the novel, thereafter electing to write only poetry—save a few short stories.

But, was Jude really Hardy’s last novel?—technically, no. The Well-Beloved was first published, by Osgood, McIlvaine, and Co., on 16 March 1897 as the seventeenth volume in the Wessex Novels edition. A story of the search for an ideal woman, its hero Jocelyn Piertson falls in love successively (at the ages of 20, 40, then 60) with mother, daughter, then granddaughter—three generations of one Portland, Dorset family. It has a fairytale quality, different in tone from Jude and Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891), and Hardy’s other great tragic novels.

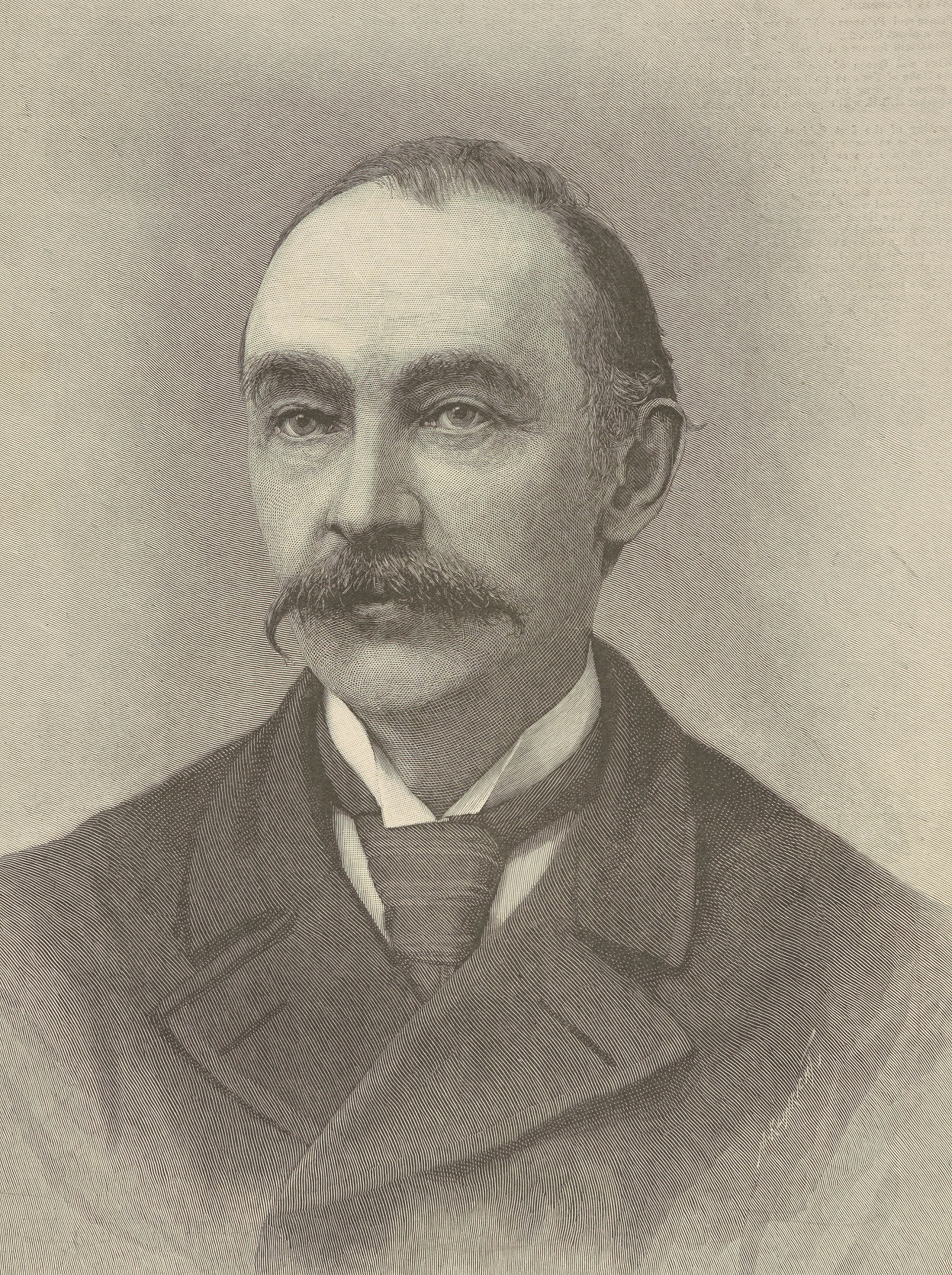

Like Hardy’s other novels, The Well-Beloved had also been first published serially, in the Illustrated London News in twelve weekly parts from 1 October to 17 December 1892. The magazine was clearly pleased to have secured this extremely famous author’s contributions, as a full-page illustration of Hardy is included before the start of the first part of the novel. New College Library holds the entire six-monthly volume of the news containing this novel in one bound volume—a fascinating piece of literary and social history from the late Victorian period.

Most notable are the first chapter and the last chapter of Hardy’s text in the Illustrated London News. Indeed, they are key to understanding the history of Hardy’s entire text. Although this serial predates Jude the Obscure, Hardy made substantial changes to both of these chapters when The Well-Beloved was published in book form in 1897. As these changes essentially altered the entire plot, it has been argued that this work of prose fiction—and not Jude the Obscure—is Hardy’s final novel. Together, both works reflect both the importance of serial publication in the Victorian period and the effects that the physical form of book production could have on the literary history of works from this period.

Throughout the nineteenth century, novels by female authors grew rapidly in popularity, and the most celebrated novelists of the period included the Brontë sisters, Elizabeth Gaskell, and George Eliot.

This period saw a push for more women’s rights—for the first time, there was a sustained movement to grant women access to the workplace, to property rights, to higher education, and, by the end of the period, to the ballot box. There were several successes: married women were granted the right to own property for the first time in 1870, the University of London first awarded women degrees in 1878 (Oxford followed only in 1920), and the suffragist movement continued to grow, with the issue debated in parliament almost every year between 1870 and 1884.

Like reform in other areas of society, though, societal attitudes were slow to change—especially in more rural areas. Indeed, throughout this period, women’s lives were still very much limited by the rigid patriarchal structures of Victorian society—with an emphasis on ‘respectability’ controlling what women could and could not do. The vast majority of women still had no access to higher education, middle-class women could only really work as governesses, and, of course, equal suffrage would only be granted in 1928—over twenty years after Queen Victoria’s death in 1901.

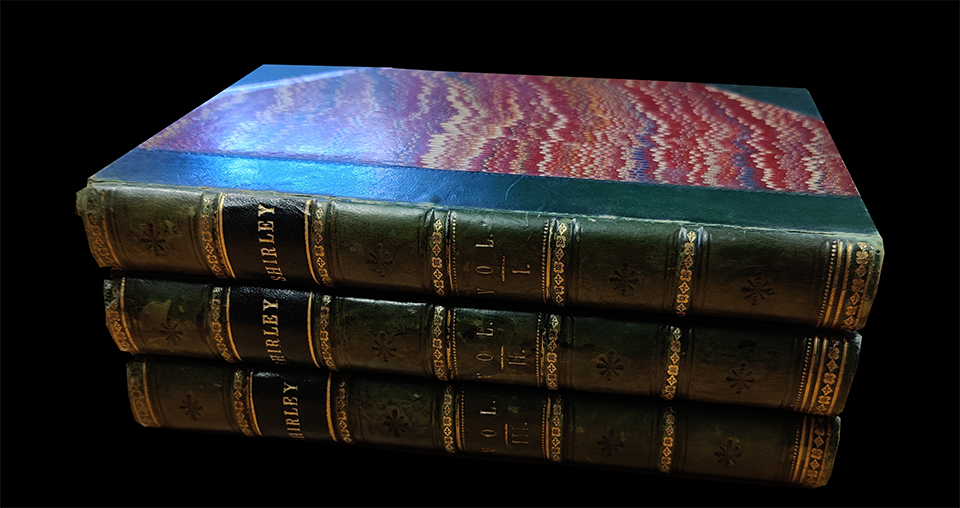

New College Library, Oxford, RS5342-RS5344

Several female authors instead used male pseudonyms as a way to bypass these patriarchal norms and to publish literature without prejudice in the male-dominated book industry. Above, you can see a first edition of Charlotte Brontë’s novel Shirley, first released in 1849. On the title-page, you can see that she published it under the pseudonym ‘Currer Bell’. This novel explored both the role of women in Victorian society and the impact of industrialisation and the Luddite riots in Charlotte’s native West Yorkshire. Male pseudonyms were also used by other authors in this period: by the two other Brontë sisters, Emily (Ellis Bell), and Anne (Acton Bell), by Mary Ann Evans (George Eliot), and by Louis May Alcott in the United States (A. M. Barnard).

This tension between increased women’s rights and the ever important notion of respectability can also be seen in the work of another great female writer: Elizabeth Gaskell (1810–1865). On the one hand, Gaskell was a groundbreaking author. She was especially significant in the history of literary biography, as in 1857 she published The Life of Charlotte Brontë—the first full-length biography penned by a female author about another female author. Although the biography was praised, its rather negative portrayal of many men featured in the book caused huge problems for the author. Indeed, it caused such controversy that Gaskell faced law-suits when her first manuscript was produced.

Gaskell was a very varied author with a wide range of styles. She may have been a pioneering author in terms of literary biography, but she was also especially concerned with societal opinion of her. She was generally always referred to as ‘Mrs Gaskell’—a deliberate attempt to highlight her respectable married status—and she was keen to point out that her main role was in the household, arguing that female authors should only write once their children had grown up.

These attitudes are reflected in probably her most famous work, Cranford. Above, you can see the first published edition of the work, which appeared in instalments in the literary magazine Household Words, edited by none other than Charles Dickens. Based on the small Cheshire town of Knutsford where Elizabeth Gaskell grew up, Cranford is an episodic tale of country life in the context of changing gender and class relations.

Cranford’s focus on female characters—who were able to live independent lives free from their husbands—made it an innovative piece of literature when it was first published. This independence is even emphasised in the very first sentence of the novel (enlarged above), with Gaskell writing that Cranford ‘is in possession of the Amazons’.

Despite this portrayal of changing gender relations, though, the women of Cranford actually resent many of the changes in Victorian society. A nostalgia for the ways of the past runs throughout the novel—nostalgia for an England untouched by the new modes of capitalism and industrialisation that challenged established traditions and customs. As such, both Gaskell and Cranford are representative of much of rural Victorian society—open to some reform, but in a gradual and controlled manner.

Many themes present in Victorian prose in this period are naturally also explored in Victorian poetry.

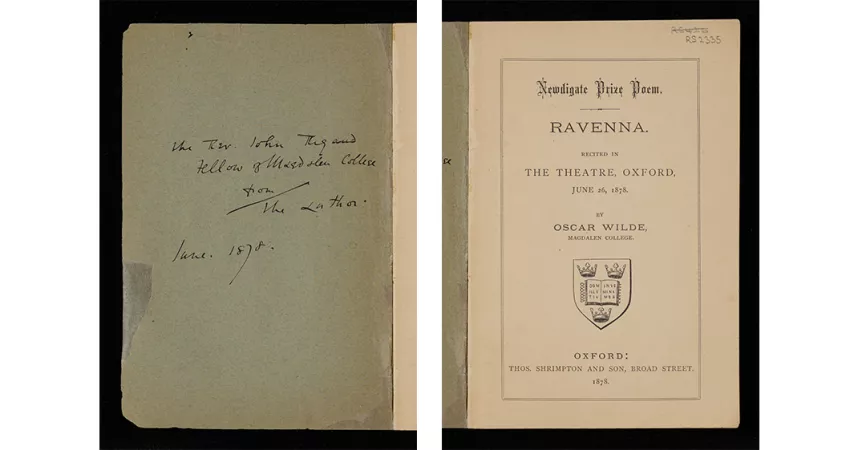

Indeed, New College’s collections also contain interesting examples of Victorian poetry that are representative of the clear conflict between respectability and innovation, reform and tradition, explored in the works highlighted above. Below, you can see a rare first-edition copy of Ravenna, written by one of the most famous poets and playwrights of the late Victorian era—Oscar Wilde (1854–1900). Click on the dots to discover more:

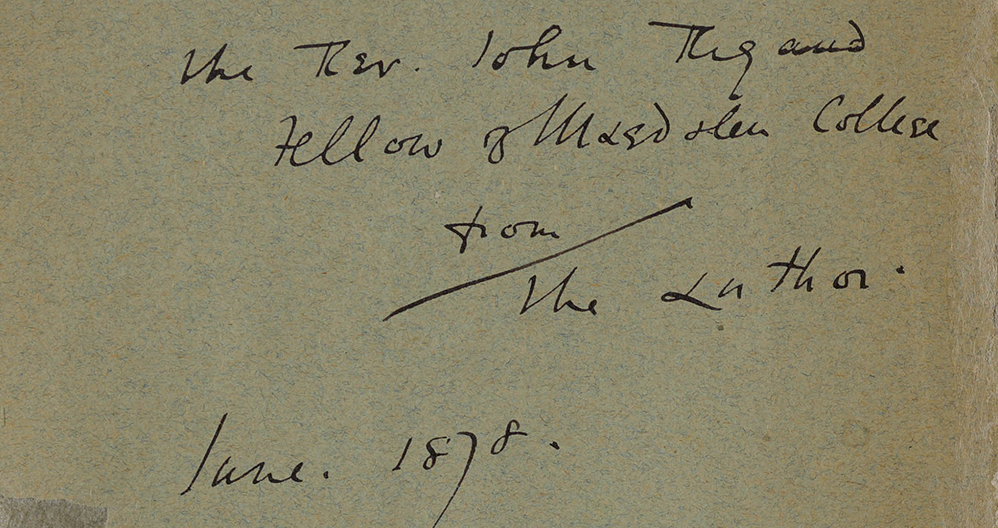

This New College copy of Ravenna is unique, as it includes a manuscript dedication from Oscar Wilde himself to a fellow at Magdalen College.

Founded in 1806, the Newdigate Prize is awarded annually to the best composition in English verse by an Oxford undergraduate student.

Ravenna was first published in 1878, making this poem Oscar Wilde’s first published work.

New College Library, Oxford, RS2335

Oscar Wilde’s life was one that combined both fame, success, and celebrity with imprisonment and scandal. This work—a 332-line poem celebrating the Italian city of Ravenna and its place in a recently unified Italy—represents the start of his literary success, with Wilde’s award of the Newdigate prize demonstrating the establishment’s approval of his work.

Interestingly, his success also links the author directly to New College’s own history, as in 1878 the winners recited their prize entries in the Hall of New College. As part of this recital, the Professor of Poetry—then John Campbell Shairp (1819–1885)—suggested improvements to the winner. Although such suggestions had invariably been accepted with gratitude in the past, Wilde proved to be the exception to the rule! He listened to all suggestions with courtesy, and even took notes of them, but in this first printing decided to not make a single alteration to his poem.

Ever a controversial figure, Wilde’s career only grew after he graduated, becoming one of the most well-known literary figures in the country, with works such as The Importance of Being Earnest enjoying great success on the London stage. Whilst at the height of his success, though, he famously met his downfall. Whilst prosecuting the Marquess of Queensbury (the father of his lover Lord Alfred Douglas) for libel, Wilde was arrested and tried for gross indecency with men. In late Victorian Britain, the public scandal caused by this trial was without precedent. Works listed above—such as Jude the Obscure and Gaskell’s biography of Charlotte Brontë—had provoked societal reaction, but the personal nature of Wilde’s trial resulted in complete societal ostracization. Wilde was sentenced to two years of hard labour from 1895 to 1897 and never recovered, showing the true limits of Victorian respectability.

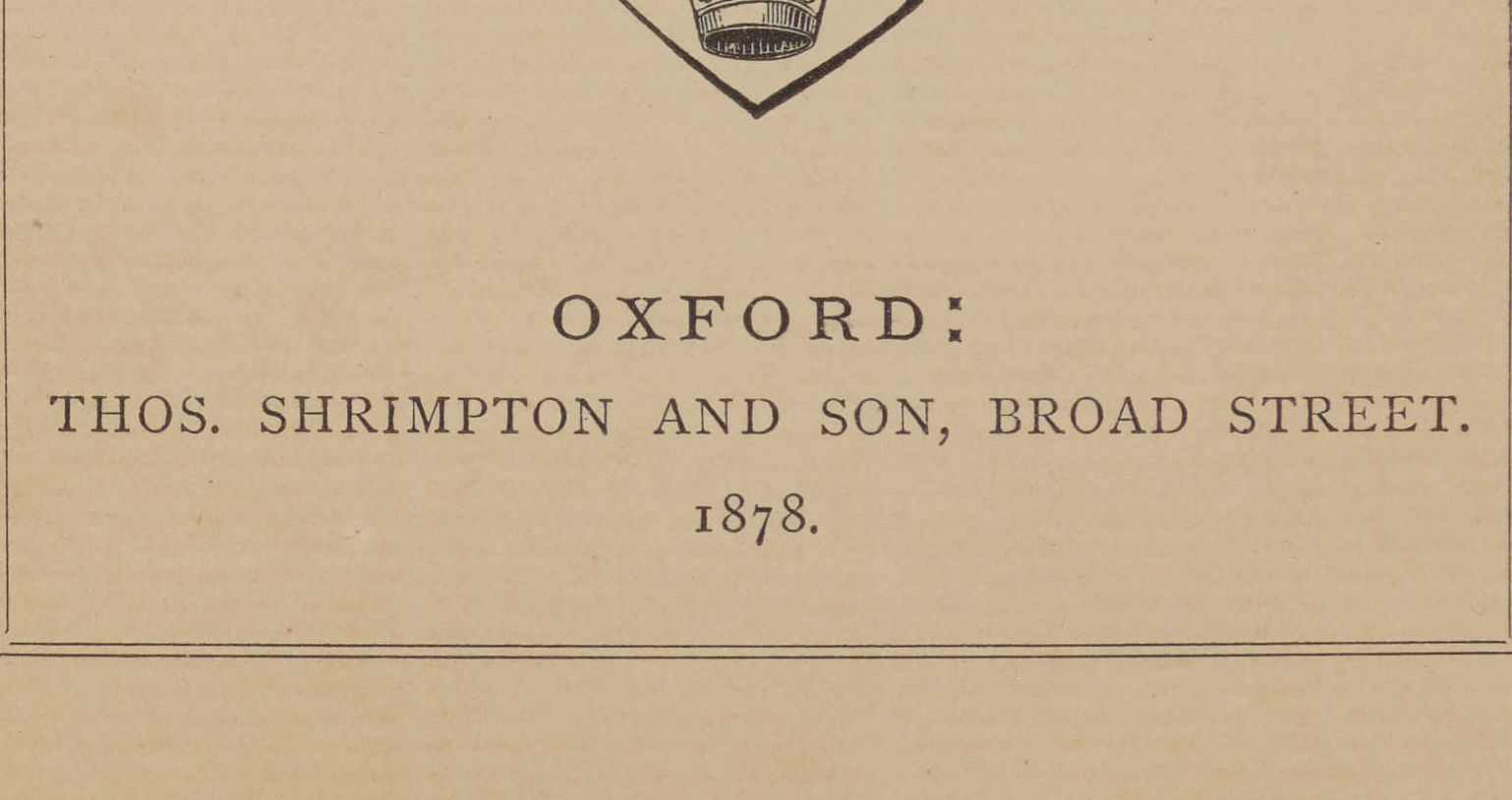

Critics have also interpreted other works of Victorian poetry as challenging societal norms in more subtle and ambiguous ways than Wilde. One key example of this in the collections at New College has to be the poem Goblin Market, written by Christina Rossetti (1830–1894) in April 1859, whilst the author was volunteering at the St. Mary Magdalene Penitentiary for ‘fallen women’ in Highgate, north London. It is, essentially, a fairy-tale gothic allegory poem of temptation, sacrifice, and redemption—sisters Lizzie and Laura are lured and assailed by the seductive, dangerous, enchanted fruit which the animalistic goblin men sell to maidens.

New College is fortunate to own several editions of this important text. In the image below, you can see the library’s oldest copy of Goblin Market—a rare second edition of the text that dates from 1865. Click on the dots to discover more:

This second edition of Goblin Market features illustrations by Christina’s brother Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882)—painter, poet, and one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Dante Gabriel also persuaded Christina to give her work the title 'Goblin Market'. She had originally wanted to call it ’A Peep at the Goblins’.

The illustration on the title-page shows the two sisters embracing, with the goblin men in the background carrying their fruit.

The frontispiece and title-page of the second edition of Goblin Market, dating from 1865

New College Library, Oxford, RS5310

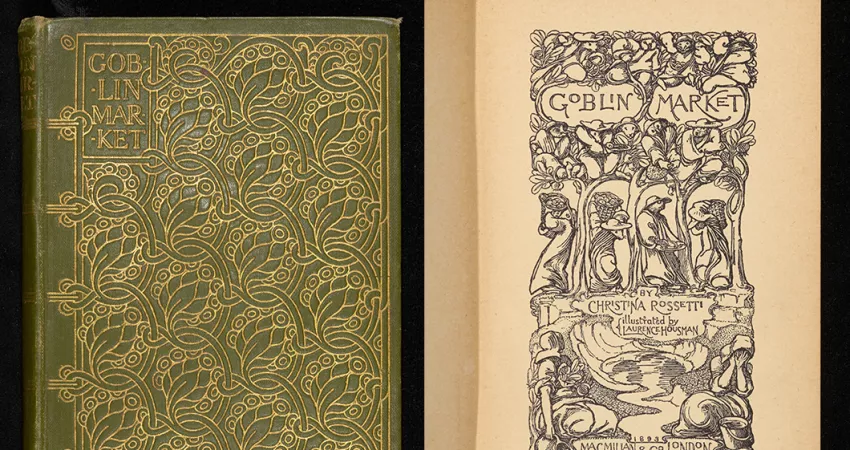

In the gallery below, you can also see two further exquisite editions of Rossetti’s text. The first shown is a beautiful edition dating from 1893 and published by Macmillan & Co. This time the text was illustrated by Laurence Housman (1895–1959)—note the art nouveau pictorial title-page on the right and the publisher’s original, elaborately gilt-decorated, bright green cloth binding on the left.

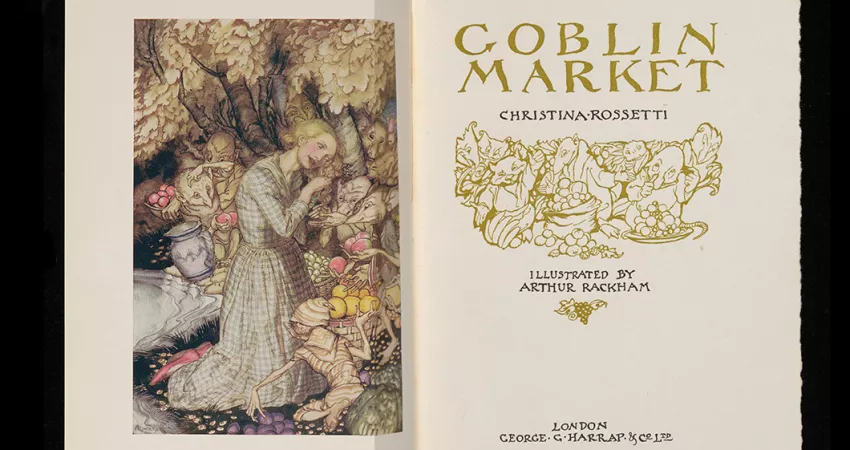

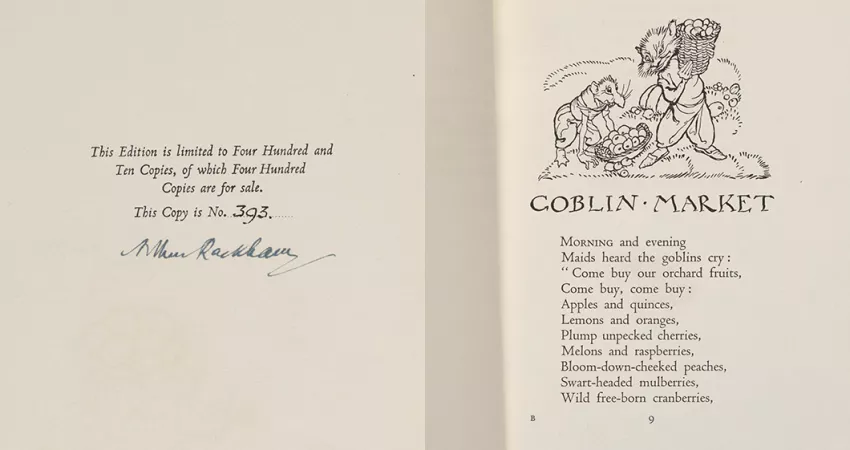

The second image in the galley shows the title-page and frontispiece illustration of a superb deluxe edition of Goblin Market, published by George G. Harrap & Co. in 1933. The final gallery image then shows the start of the poem, as well as revealing that it is a limited edition, with the New College copy being number 393 of only 410 numbered copies. The signature below the limited edition statement belongs to Arthur Rackham (1867–1939), who painted the superb illustrations that appear throughout. In total, there are four colour plates and nineteen black and white drawings in this sumptuous edition of the text.

Rossetti, rather disingenuously, claimed that she ‘did not mean anything profound by this fairytale’. Both its innovative style (it never conforms to a set rhyme scheme or metrical pattern) and its ambiguous message, though, have made it the subject of various different interpretations. In the decades after its publication, it has provoked feminist, Freudian, Marxist, and queer theory readings. Lizzie’s fall and subsequent restoration, for example, have been interpreted as support for the possible redemption of fallen women—a profoundly radical view in Victorian Britain. Likewise, it has been interpreted as a parable of female resistance and solidarity, as well as of lesbian empowerment. Rossetti’s real intention behind the poem may never be known. In reality, Victorian society may have prevented her from making her ideas more explicit in the poem. Its subtle message, open to interpretation, though, created a quietly revolutionary text—one that blurred the lines of traditional Victorian notions of respectability.

Victorian literature is well represented in New College Library’s collections.

The College has been fortunate to collect first editions and early works from this important period of English literature. As we have seen, this was a time of bibliographical innovation, with new forms of prose work and poetry exploring the impact that industrialisation, nascent capitalism, and new forms of technology were having on wider society. It was a time of both constant change and constant reaction towards change, with a gradual movement towards reform and liberalisation. This trend would only accelerate in subsequent decades—throughout the tumultuous twentieth century and into the modern period.